Author - Charles Wilson with Graeme J W Smith - My father Robert Wilson was born in the small industrial village of Brora, in the remote North Eastern Highlands of Scotland in 1914. With electricity distributed from its wool mill, Brora was then known as the "Electric City" and also had a coal mine, brickworks and whisky distillery. As a boy, Rob was inspired by the rapid expansion of flying and aircraft technology, making and flying both kites and model aircraft.  The studious Rob won a Sutherland County Scholarship which allowed him to pursue an apprenticeship at the De Havilland Aircraft Company in Hatfield near London in 1933. Rob progressed well within De Havilland, gaining ground engineers’ licenses for several aircraft types. He also obtained a pilot license. Apprentices started by making their own tools and toolbox from raw materials. For the back of his toolbox, Rob salvaged the floor from UK aviatrix Amy Johnson’s de Havilland DH.60 Gipsy Moth JASON which was in the shop for repair after her record-breaking solo flight from the UK to Australia in 1930. The toolbox and tools are now used by his grandson Felix.

The studious Rob won a Sutherland County Scholarship which allowed him to pursue an apprenticeship at the De Havilland Aircraft Company in Hatfield near London in 1933. Rob progressed well within De Havilland, gaining ground engineers’ licenses for several aircraft types. He also obtained a pilot license. Apprentices started by making their own tools and toolbox from raw materials. For the back of his toolbox, Rob salvaged the floor from UK aviatrix Amy Johnson’s de Havilland DH.60 Gipsy Moth JASON which was in the shop for repair after her record-breaking solo flight from the UK to Australia in 1930. The toolbox and tools are now used by his grandson Felix.

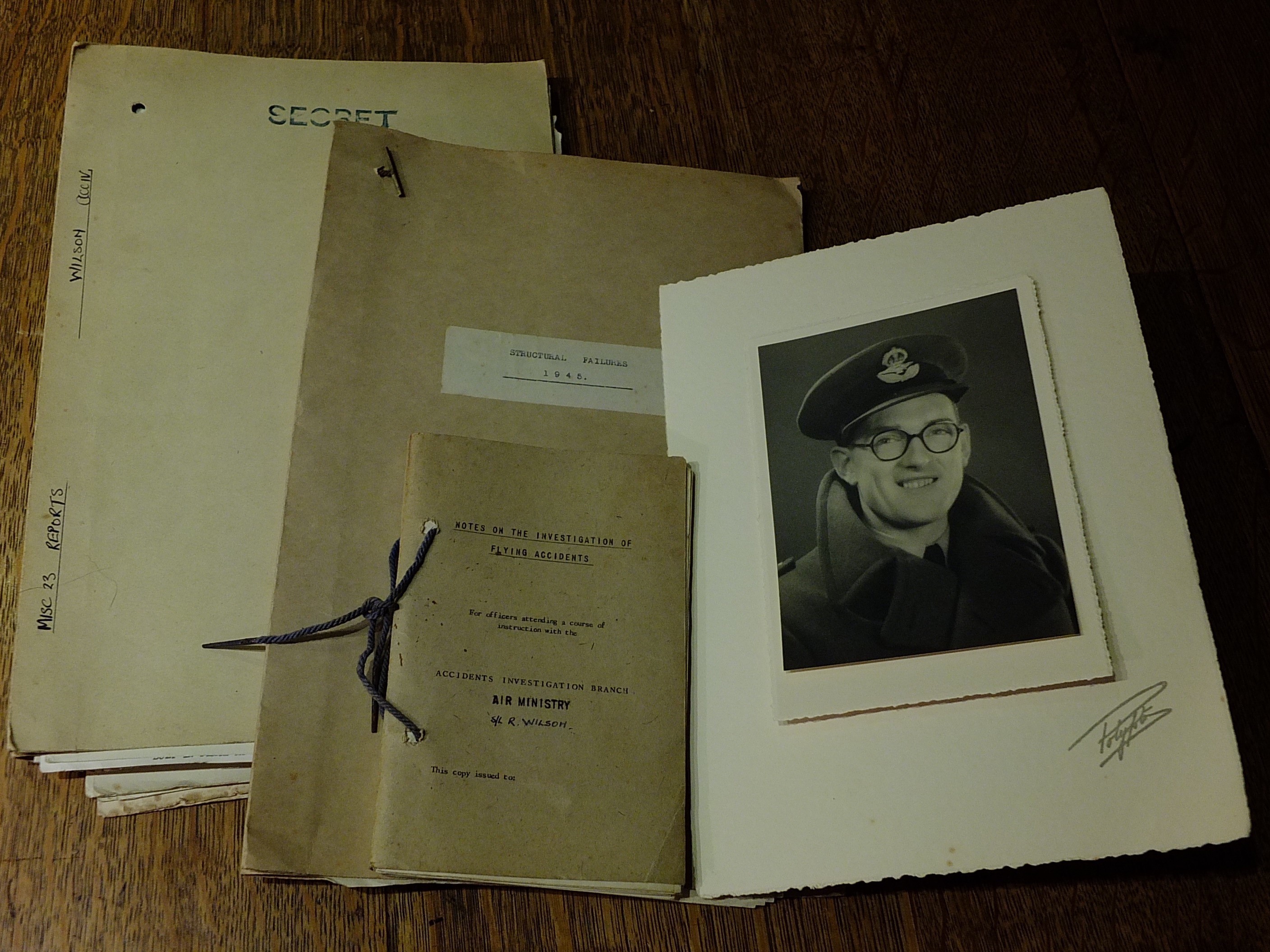

WWII saw Rob volunteering as a pilot but his medical classification and reserved occupation meant he was not accepted for combat duties. Instead he was involved in ‘ab-initio’ flight training. He was also lucky to survive a parachute test that ended in the water. His skills and experience ultimately led to his recruitment into the Royal Air Force Accident Investigation Branch. Rob’s boss was F.P. (Fred) Raynham, notable amongst other things for a transatlantic flight attempt in 1919. While Fred’s attempt failed, he donated his remaining stock of fuel to Alcock and Brown’s successful Atlantic crossing in the same year. Rob was quickly promoted to Squadron-Leader and then Wing-Commander. In addition to their expertise, it was quickly determined that accident investigators needed some rank in order to demand that wrecks were left undisturbed, to obtain access to maintenance records and other resources they would need to do their work. A clearly non-flying and spectacled Wing Commander must have raised more than a few eyebrows.

| Report Format The format established during the war will be familiar to anyone reading modern reports. - A summary of what happened, - A record of the aircraft build, hours on the airframe and engines, modifications incorporated, maintenance performed. - Crew experience and hours on type (often woefully little by modern standards), - Wreckage examination - Witness statements - Radar and Searchlight battery records - Any testing performed on parts of the wreck - A fuller account of the investigation, what probably happened and what had been considered and what had been discounted. - A “Conclusion” was considered a firmly established cause of the accident. - An “Opinion” was just that – lacking firm evidence – an opinion as to what probably happened. A factor not examined was the toxicology of the deceased. However, close attention was paid to the oxygen systems and whether or not they were likely to be functioning – hypoxia leading to anoxia being well understood. |

The accidents investigated were not operational losses. They were the type that in modern terms would be considered the purview of the US NTSB or UK AAIB. Unexplained crashes, structural failures, piloting errors. The aim was the same as now – to determine design defects in aircraft and equipment, maintenance procedures and pilot training deficiencies and so reduce expensive loss of lives and equipment. All was conducted under the pressure of war and the complication of rapidly evolving aircraft designs. Under the leadership of Fred Raynham and later Vernon Brown, Rob and the other AIB investigators established the principles and practices used in UK Aircraft Investigation which are used to this day.

Post war Rob returned to Brora where he ran the local coal mine and brickworks, taking over in 1954 as managing director. His great love of fishing combined with craftsmanship and engineering skills led to a re-thinking of the traditional split cane fly fishing rod. Hours of hard work in a small workshop over the village bakery transformed into the business “Rob Wilson Rods and Guns” which sustained his growing family through the 1980’s. Like all fishermen he was always a great storyteller and we were often regaled with his wartime aviation tales. On his death while clearing out the proverbial attic I made a fascinating discovery. My father had actually kept a copy of many of his wartime investigations, together with summaries of structural failures of a variety of aircraft types. They covered a period from early 1940 through August 1945. Reports cover over 20 types, including the Avro Lancaster, Mustang, Spitfire and Vickers Wellington. Because of his association with De Havilland – most of the reports cover the DeHavilland Mosquito.

Post war Rob returned to Brora where he ran the local coal mine and brickworks, taking over in 1954 as managing director. His great love of fishing combined with craftsmanship and engineering skills led to a re-thinking of the traditional split cane fly fishing rod. Hours of hard work in a small workshop over the village bakery transformed into the business “Rob Wilson Rods and Guns” which sustained his growing family through the 1980’s. Like all fishermen he was always a great storyteller and we were often regaled with his wartime aviation tales. On his death while clearing out the proverbial attic I made a fascinating discovery. My father had actually kept a copy of many of his wartime investigations, together with summaries of structural failures of a variety of aircraft types. They covered a period from early 1940 through August 1945. Reports cover over 20 types, including the Avro Lancaster, Mustang, Spitfire and Vickers Wellington. Because of his association with De Havilland – most of the reports cover the DeHavilland Mosquito.

An early frustration was civilians souvenir hunting from wrecks. During the Battle of Britain in 1940, every kid tried to collect bits of shrapnel, spent bullets or parts of downed German aircraft. In subsequent years the ongoing pilfering from British wrecks was proving a serious hinderance to investigations. The loss of one Mosquito was put down to a faulty spinner fastener that had allowed the spinner to detach, knocking off an undercarriage door, which had then knocked off the aircraft fin (vertical stabilizer) leading to loss of control and loss of the aircraft and crew. A classic accident chain.

While there was other contributing evidence, the vital spinner was missing. Witnesses had “seen a boy playing with it” but all efforts to trace the boy and spinner were in vain. It became such a problem that the Air Ministry Chief Inspector of Accidents produced a short film for showing in cinemas. “Bits of Our Aircraft Are Missing” outlined how pilfering or moving of even the smallest and most innocuous looking part could delay a thorough investigation and lead to more lives lost. It made a sobering contrast to the normal and constant films about how to make meagre food rations go further.

My father's wartime boss Vernon Brown appears at the end of this movie.

As a kid I used to meet him when he and my father had lunch.

When the Mosquito entered service there was a structural failure rate of one aircraft per 5,400 hours flown. By the end of 1943 the aircraft was debugged, modifications were in place and the rate had improved to 1 aircraft per 15,735 hours in some marks. But by the end of the war the figure was back at one aircraft per 8,960 hours. Increased war store loads and changes in roles meant that the factors of safety that were originally built into the aircraft were compromised. “Hamfisted” heavy bomber pilots converting from the strong Avro Lancaster to the “light twin” were contributing factors as they hauled the wings off Mosquitos at a rate of about two a week. Early deployments in Australia showed a staggering failure rate of one aircraft per 1,000 hours flown!

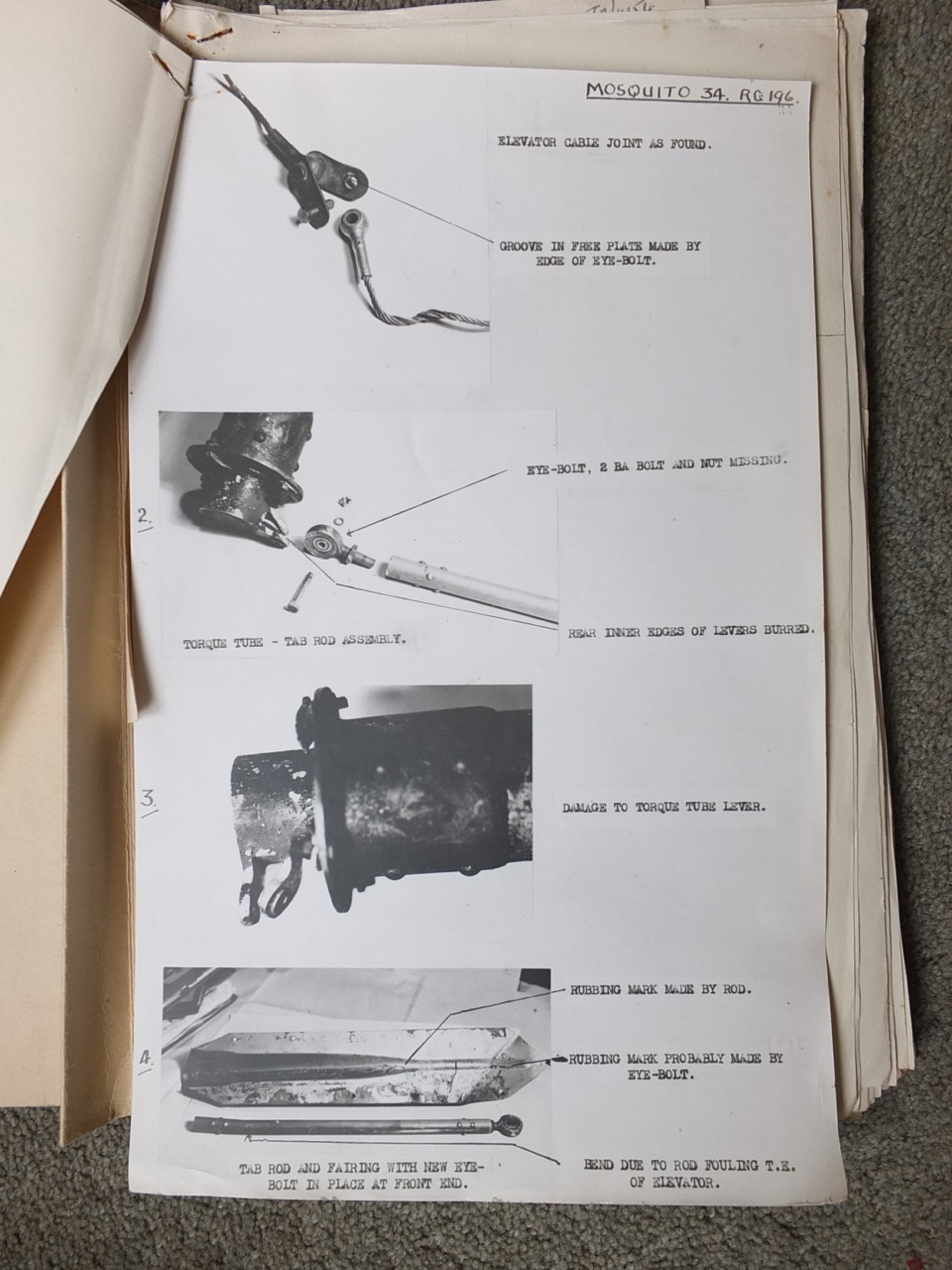

| Other regularly recurring factors included - Early fabric covered elevators failed when the torque tube and ribs detached caused by horn loads (Ultimately resolved by fabricating the whole elevator from metal). - Oxygen and hydraulic bottles with iced up relief valves that burst and destroyed aircraft structure. Similarly – Extinguisher bottles under engine cowls exploded when improperly installed and exposed to exhaust heat. These blew off cowls and destroyed oil feed lines causing engine failures. - Hatches had a tendency to depart the aircraft when the airframe was torsionally loaded (Catch redesign and a stiffening strake were applied) - Quick release fasteners on spinners that didn’t engage (modification included an inspection port to be sure they had) - Drop tanks supposed to be released in straight and level flight damaged or destroyed wings when released under maneuvering loads - Undercarriage door failures leading to loss of control when they struck the tail of the aircraft. Often caused by gear locks failing and gear dropping unexpectedly. (Gear locks were improved and door catches were modified but doors remained vulnerable to being hit by other debris). - Other structural failures of wings when pulling up. Usually aerobatics or after “beating up” airfields. “Unauthorized Manouevers.” - Failure of leading edges above the “in wing” radiators (modified by strengthening) - Elevator rigging tension issues (Solved by the introduction of tensiometers instead of riggers’ judgement) - Spins often led to a side loaded engine being thrown off its mounts leading to the loss of the aircraft |

A vital report was the quarterly summary. There were a lot of wing failures in early Mosquitoes and it was vital to discover if the “Wooden Wonder” was perhaps a “Wooden Dud”. A series of criteria were established for examining if wings had failed in “upforce” or “downforce” (positive or negative G) and if wing skins had detached, ruptured or buckled. Early findings showed a combination of gluing problems (the glue type was changed) and pilot training. Pilots were simply not used to how fast and slippery the Mosquito was. They were overstressing aircraft pulling out of dives that had “got away” from them.

Upper radiator fairings on the wing leading edge were often overstressed, detached and then wings failed. As early as June 1942 there were recommendations to fit “anti-G” tabs to elevators to prevent abrupt dive recoveries. However it remained a constant problem throughout the war and one of the last reports Rob produced in August 1945 was from the loss of an aircraft that was testing these devices. They didn’t work at high speed and caused pitch excursions that led to loss of control and breakup of the test aircraft midflight. The pilot was lucky enough to be thrown clear and pull his parachute. The observer aboard filming the trials - not so.

With a thorough understanding of the issues that could cause structural breakup - a real and serious concern discussed in a later war report was that the aircraft was not capable of withstanding extreme handling that might be needed when taking evasive action. Metal planes might bend and still make it home, even if never to be used again. Mosquitos didn’t, they broke up.

The Mosquito was never considered “Fully Aerobatic”. Indeed, aerobatics in Mosquitos were always banned but a lot of pilots tried – especially test pilots – and they often died as a result. Speed to escape attack remained the recommended defence. Reports of night test and training flights detail aircraft that “spun in” for no clear reason. If the investigation found that the aircraft had been airworthy, the instruments and oxygen system were functioning then the “opinion” was “pilot error”. Planes diving out of clouds often broke up. Given the often-low pilot hours and the poor weather conditions over the UK these became an early examination of “human factors”. “Spatial Disorientation”. Such was the pressure of war.

The Mosquito was never considered “Fully Aerobatic”. Indeed, aerobatics in Mosquitos were always banned but a lot of pilots tried – especially test pilots – and they often died as a result. Speed to escape attack remained the recommended defence. Reports of night test and training flights detail aircraft that “spun in” for no clear reason. If the investigation found that the aircraft had been airworthy, the instruments and oxygen system were functioning then the “opinion” was “pilot error”. Planes diving out of clouds often broke up. Given the often-low pilot hours and the poor weather conditions over the UK these became an early examination of “human factors”. “Spatial Disorientation”. Such was the pressure of war.

Contributing to difficulties with recovery from disorientation were aircraft that were becoming less and less stable as the war progressed. Loaded with greater war loads and becoming close to CG limits - the Mark 34 Long Range Photo Reconnaissance Mosquito with a fuselage full of cameras and film and a full fuel load was considered unrecoverable from an engine out on take off. Mosquitos used as Pathfinders and heavily loaded with marker flares and fuel so they could spend time on target were also very vulnerable. Adjusting balance weights in the aircraft rigging and balance horns on the elevators could compensate to a degree. However, this compensation led to wings being vulnerable to strong control inputs in turbulence and more than one wing was torn off by pilots trying to right their aircraft in level but turbulent flight. The problem was compounded after aircraft had dropped their loads and burned off their fuel, the modifications that got them to the target now made them unstable at the other end of their flight envelope on the way home.

The Mosquito had a reputation for poor single engine performance. 50% of loss of control accidents were considered to have occurred in straight and level flight when an engine failed. Trials were performed with a Mosquito in various speed and CG configurations when an engine was deliberately “chopped”. As expected, the aircraft rolled onto its “dead” engine. Then the nose would drop, the wings would go vertical, the gyros would topple and the plane would enter a spiral dive. The pilot had about 1½ seconds to “get it right” and catch the aircraft as it went through a 45 degree bank or lose the aircraft. Toppled gyros in cloud was disorientation disaster. With no easy design change possible – all that could be done was to emphasize the issue in training and the “Pilot Notes” – the RAF version of a Pilot Operating Handbook.

Another report outlines the high fatality rate when things went wrong. Cramped accommodation was a factor and the overhead escape hatch for the pilot was hard to escape through. If the aircraft broke up in the air – both crew rarely survived. If the crew were baling out of an aircraft that was damaged but under a degree of control – navigators survived far more often than the pilots who were trying to hold the aircraft level while the navigator donned their parachute. Pilots then often pushed (actually kicked) the navigator out before losing control. However more than one pilot was saved by the metal armour plate behind his seat breaking free as the aircraft tumbled, cutting open the cockpit, and allowing him to be thrown clear.

While it might appear from all the foregoing that the Mosquito was actually a “dud” – in the context of wartime operations it actually had a low operational loss rate combined with adaptability to multiple roles. It needed careful construction, maintenance, monitoring, upgrading and handling. Just like all other types. When this was done – it was a highly effective aircraft. The material is currently still in my care. The digitized reports pertaining to Mosquitos has been shared with known current operators and restorers. The future of the whole collection is likely to be a museum.

Listen also to Podcast – “History of Aircraft Investigation” - https://www.aerosociety.com/news/history-of-accident investigation/